How to find great work

I. Ideal of work

Last year, I changed my mind about work. I believed in a strict work-life balance, working enough to meet our needs and enjoy the rest of our time. I’ve now realized that by seeing work as something to protect or balance against, I was stunting the potential of a type of work you could enjoy and would be OK spending hours on.

The concept of work-life balance alienates work as something to balance against. As something separate from life. A cruel requirement to earn a living.

In an ideal world, I’d like work to be closer to Khalil Gibran’s vision in “The Prophet”:

“Work is love made visible. And if you cannot work with love but only with distaste, it is better that you should leave your work and sit at the gate of the temple and take alms of those who work with joy.”

Work as something that gives us dignity and fulfillment:

“And when you work with love, you bind yourself to yourself, and to one another, and to God.”

“For if you bake bread with indifference, you bake a bitter bread that feeds but half man’s hunger.”

Although it can take time to get to this point. It’s a worthy journey.

II. Finding your work: avoid bullshit first

Many of us have to go through many jobs we like and don’t like to find work we enjoy. From each of them, we learn something. Some jobs spark your curiosity, and others that can be life-draining.

In one of my first jobs, I worked as an analyst for a bank in Utah. I would have to wake up before 6 am, commute for an hour in the winter, and then sit at my desk filing forms for wealthy people for 10 hours. By the time I left work, it was dark again.

My manager would drop a stack of 15 folders on my desk. I’d open each one, read it, and manually type the information on the bank’s registration website.

Once done, I’d go to the printer, print about 500 pages of new forms, organize them, and head back to my desk. On my second day at the job, one of the interns cried near the printer station, lamenting she had to sit idle at the printer for hours each day.

This experience taught me there’s a whole category of jobs where your tasks can feel meaningless. Where you know at your core that the job could be automated or exists to check a box.

David Graeber in his book “Bullshit Jobs” talks about these types of jobs.

“A bullshit job is a form of paid employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence even though, as part of the conditions of employment, the employee feels obliged to pretend that this is not the case.”

“Huge swathes of people spend their days performing jobs they secretly believe do not really need to be performed.”

“The moral and spiritual damage from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul. Yet virtually no one talks about it.”

We could argue that opening accounts for trust funds has a use, and it’s not a bullshit job. However, since we worked with paper forms that we know could be automated, it put it back in the “bullshit job” category.

We were a buffer between the registration site and wealthy individuals who wanted to avoid filling out forms online. The bank didn’t want to force them either.

A survey from the UK said about 37% of British workers claimed their job “didn’t make a meaningful contribution to the world.”

Reading through the book, I found my past job nailed a few of the Bullshit Job:

- [] Do you believe that if your job didn’t exist, it wouldn’t make any difference to society or anyone’s well-being?

- [] Are many of your tasks or responsibilities contrived to keep you busy, rather than to accomplish something practical or beneficial?

- [] Do you spend significant time on paperwork, meetings, or administrative tasks that seem to have little overall effect?

- [] Does your job involve solving problems that shouldn’t exist or could be easily avoided?

III. Finding your work: try out things

Once you’ve decided you want to work on something meaningful, trying out many things is essential. Especially early in your career.

Paul Graham, in his essay “How to do Great Work,” explained how the way to know what to work on is by working. You’re going to guess wrong many times, which will teach you what jobs you enjoy.

If you don’t know what to work on; take chance meetings, make yourself a big target for luck. Try lots of things, meet people, read books, ask questions - Paul Graham

To find out I enjoyed programming, I worked as a CAD designer, a business development intern for an oil company, an operations analyst for a bank, and a management consultant for healthcare companies.

Each of those experiences was early in my career, and while some were better than others, they all gave me hints about where I felt most engaged.

Some jobs I did to seek approval from my parents, others I chased for prestige and the allure of travel. Neither of these things fulfilled me.

Paul Graham warned in his essay of “pretentiousness, fashion, fear, money, politics, other people’s wishes, and eminent frauds. Stick to what you find interesting.”

I learned that to avoid these traps, you need to ask yourself if you’re engaged in your job. A sign that you’re in the right field is that it becomes increasingly attractive to you as you learn more about it.

In academic environments, especially in graduate schools (i.e., MBA), it’s easy to fall into memetic thinking, that is, wishing for what others want. Wanting to be in a big tech company, or in a top consulting firm, or in a hot start-up.

While those are commonly promising avenues for people to develop, they can be fraught with people resenting it’s not what they thought it would be.

Once you try a few things and find a field that’s become increasingly engaging with time, The next step is to focus.

IV. Exploiting your interest, focus

Focusing can be exponential. If you’re focused on 4 things, moving to 3 can be a 20% jump in productivity. But if you move to 1, it can be a 400% jump.

Almost everyone I’ve ever met would be well-served by spending more time thinking about what to focus on. It is much more important to work on the right thing than it is to work many hours. Most people waste most of their time on stuff that doesn’t matter. - Sam Altman

I’ve learned that I can’t be very productive working on things I don’t care about or don’t like - Sam Altman

Don’t divide your attention too thinly; be professionally curious about a few topics and idly curious about many more. - Paul Graham

Focusing is more about picking what to work on vs. finding out what note-taking tool will give you an edge in organizing your information. Finding out how to do something productive that shouldn’t have been done in the first place is useless.

I’ve fallen trapped in this many times; I’ve spent hours figuring out how to organize a project in Notion or browsing Reddit forums figuring out what the best book for a subject is. Instead of opening a book that’s good enough and getting started working.

I’ve come to realize that it doesn’t matter which tools you use, it does matter that you pick the project you want to work on carefully and saying no to distractions along the way.

V. Learn about the field

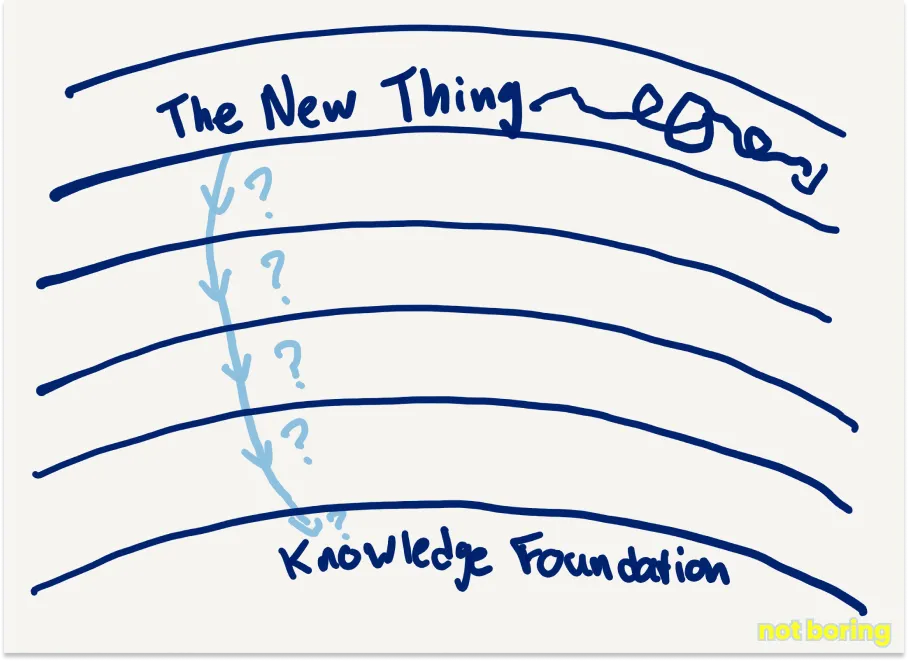

To succeed in a field, you need to have a solid foundation to layer new knowledge.

In Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood passage, Nagasawa tells the book’s protagonist, Toru Watanabe, that he only reads books whose authors have been dead for at least thirty years.

He continues saying “If you only read the books that everyone else is reading, you can only think what everyone else is thinking.”

How do we build foundational knowledge? Ask yourself what concepts in my field are not going to change in the next 5-10 years.

In computer science, it means knowing about algorithms, data structures, computer networking, or how operating systems work.

There might be many trends in Generative AI models. Still, they will all have to be run on computers, use networking to communicate with each other, and apply linear algebra to predict the results.

“I very frequently get the question: ‘What’s going to change in the next 10 years?’ And that is a very interesting question; it’s a very common one. I almost never get the question: ‘What’s not going to change in the next 10 years?’ And I submit to you that that second question is actually the more important of the two – because you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time. - Jeff Bezos

V. Doing meaningful work

Assuming you’ve found an area that interests you and learned enough to be helpful to any company. The last step is doing great work.

Many times, it’s hard to figure out if what you’re doing will make a difference. Finding what to work on is a combination of luck and persistence.

In his talk, Running Down a Dream, Bill Gurley talked about a young musician named Robert Zimmerman who shows this idea.

Robert loved music, and in this early photo he’s got a drum. He got a guitar when he was 10 years old, and by high school was playing in a band regularly. They used to cover Elvis and Little Richard. His yearbook says that he’s likely to join Little Richard.

He didn’t have a lot of money. Back in the time, you could walk into a record store and listen in a booth. He would do that for hours and hours and hours. He became friends with people that also liked folk music, but had money. He would go to their house and listen to their record collection.

The next thing that happened, I think, is one of the most ambitious actions anyone that I know has taken to pursue their dream job. He hitch-hiked from Minneapolis to New York City. He had a guitar, a suitcase and $10, and it’s 1,200 miles. If you ask him today why he did it, he’ll talk a little bit about chasing the performers, so this is Dave Van Ronk, Peggy Seeger, the New Lost City Ramblers, these were people he was listening to in Minnesota, but these people were in New York City, and so he wanted to see them.

He went to New York. He found Woody Guthrie. He used to perform for him. Then he started hanging out at these three venues, the Café Wha?, The Gaslight Café and Gerde’s Folk City. This was the epicenter of folk music at the time, and he would sit in each of these venues for hours upon hours and study what the other artists were doing.

He was studying, studying, studying. He got a big break. He was asked to open for John Lee Hooker at Gerde’s one day, and his career got started.

This gentleman is Joe Hammond. He was the producer for Aretha Franklin, Billie Holiday, Count Basie. One day he walked in and found this gentleman, 1961. I think he’s 22, 23, something like that. The next year, Robert Zimmerman changed his name to Bob Dylan.

We may have to try different things to find out what we like. But when we do, we owe it to ourselves to care about it. To learn, focus, and share our work with others.

References:

- Bill Gurley, Running Down a Dream.

- Gibran, Khalil. “The Prophet.” Alfred A. Knopf, 1923.

- Sam Altman. On Productivity

- Paul Graham. How to Do Great Work.

- Pace Yourself by Not Boring.